Afrocentric Fashion For Beginners: Complete Style Guide

Discover the rich history of Afrocentric style, its modern influences- and how to style it for your unique taste.

8/28/202531 min read

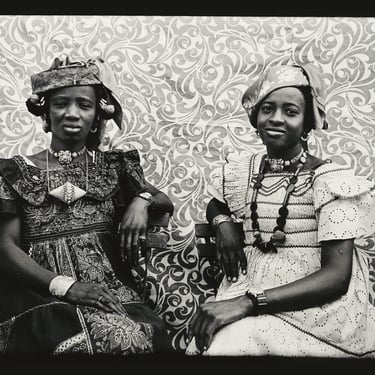

We are witnessing the rise of African culture, it’s not obvious but you can feel it. Society is charged with our culture, by the beauty of style, the power of our bodies, the force of creative energy- and nothing embodies all of these aspects as neatly as the rise of Afrocentric fashion. On every continent, in nearly all fashion circles worth talking about, the influences of Africa give life to unmatched style, and for good reason.

The meteoric rise of Afrocentric fashion is born of a continent whose textiles tell stories older than written language, yet remains alive and well in the feeds of social media’s most fashion-forward creators. From the birthplace of humanity, its purest expression was given life through every garment passed down from time immemorial- and you can feel it. In the cuts, in the colors, in the symbols that voice eons of artistry, pain, joy, reverence- African fashion is truth. That’s why it’s on the rise, and that is why it’s not going anywhere.

However, in this brief moment in time that we are on this beautiful planet, we should embrace our place in this beautiful tapestry of expression by embracing African style and fashion. If you’re reading this article I hope that is the reason you came, and I hope in some small way, this will help you. Below is an African fashion guide that will give you a better understanding of the Continent's style past, it's present trends, and hopefully an idea of your future Afrocentric style. If you've ever been interested in African fashion, but are unsure where to start- begin here!

But to understand Afrocentric fashion’s global influence, we must start where it began — in the villages, markets, and royal courts of Africa’s many cultures.

The Brief Birth and History of African Fashion

You’re going to hear me say this several times in this article, but I say this from a place of honest reverence; THERE IS NO WAY I COULD COVER OR DO JUSTICE TO ALL OF THE FASHION HISTORY OF THE AFRICAN CONTINENT. However for the sake of offering a beginner’s guide to Afrocentric fashion, I hope that the topics we cover will be at least sufficient. That being said, the African continent is a mosaic of over 3,000 ethnic groups, each with its own textile traditions, silhouettes, and style codes. Here are some of the general regions:

West Africa

Countries: Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, and more.

West Africa is one of the world’s most influential fashion powerhouses, with a long-standing tradition of textile artistry. Not only are they dominant in these industries producing fashion and textiles, countries such as Mali and Burkina Faso are global pillars for the harvesting and export of cotton- sartorial gold. These countries were once defined by much different boundaries, but the Ancient kingdoms that made up these regions like Mali and Ghana (as early as the 8th century) thrived on gold, salt, and fabric trade routes. Indigo dyeing, particularly in Mali and Nigeria, was both a practical skill and a spiritual practice.

In the Ashanti Kingdom, kente cloth once reserved for royalty was woven with symbolic patterns and colors. In Mali, the craft bogolanfini (mud cloth) was perfected with hand-dyed fermented mud, illustrating ancient stories through geometric motifs. Nigerian Aso Oke — a richly woven fabric of silk and cotton — has been worn for centuries during weddings and coronations.

While these different garments represent unique kingdoms and periods of cultural significance, much of the clothing communicates a common thread of social status, lineage, and even current life events. Fabrics are chosen with intention — a certain print might announce a marriage, mourn a loss, or celebrate a new child.

In today’s age, Lagos and Accra reign supreme as the style capitals of West Africa, with visionary designers blending traditional weaving with avant-garde cuts. Ankara wax print, while originally European in manufacturing origin, has become a West African cultural staple, reimagined in everything from streetwear to haute couture.

East Africa

Countries: Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Somalia, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi.

East Africa’s style history is deeply tied to the Indian Ocean trade, which brought fabrics, beads, and ideas from as far as India, Persia, and China. Swahili coastal cities like Mombasa and Zanzibar thrived as cultural crossroads. Arab traders introduced cotton, silk, and intricate embroidery techniques as early as the 10th century.

Some of the most notable fashions of the region and time include the kanga and khanga in Kenya and Tanzania are printed cotton wraps with Swahili proverbs — a literal wearable language.

Further north in Ethiopia, the habesha kemis is a white cotton dress with beautiful, detailed handwoven borders, often seen during Ethiopian Orthodox Christian celebrations. In the vast grasslands occupied by the Maasai, beadwork and shúkà (red-checkered wraps) can be seen adorned by many, vibrant symbols of identity, age group, and social standing.

Universally these clothing and adornments often signal life stages, marital status, and clan. The integration of imported fabrics into indigenous styles reflects centuries of adaptability.

Southern Africa

Countries: South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Eswatini, Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, Angola.

Southern Africa’s styles combine indigenous craft, colonial-era adaptation, and post-apartheid identity politics.

Indigenous communities like the Zulu, Xhosa, and Ndebele have long traditions of beadwork, body adornment, and geometric pattern-making. The Basotho blanket is both a practical winter garment and a cultural emblem. Distinct cultural staples like the Xhosa attire uses monochrome beading and patterned fabrics to signify rites of passage. Ndebele mural patterns translate seamlessly into textiles and jewelry design.

Like many cultures throughout the continent, these articles of clothing are often worn to mark ceremonies — weddings, initiations, and harvest festivals — and reflects clan pride.

Modern Established and up-and-coming designers like Thebe Magugu and Laduma Ngxokolo (of MaXhosa Africa) reinterpret traditional beadwork and knit patterns for the runway, winning global fashion awards.

North Africa

Countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Sudan.

North African fashion blends Arab, Berber, and sub-Saharan influences in garments like the Moroccan Djellaba or the hooded Burnous, their silhouettes as fluid as the desert sands they cross.

Trade routes such as the Trans-Saharan caravan paths, the Nile’s lifeline, and the Indian Ocean spice corridors carried fabrics, dyes, and decorative techniques between cultures. Indigo from West Africa found its way east; Moroccan leather traveled south; and beads from Venice were reimagined in Zulu patterns.

The beauty of North African fashion history is that much of it is well recorded. We have several thousand years of imagery, artifacts, and documentation to verify the rich sartorial history of the region. Ancient Kemetic (Egyptian) linen tunics and beaded collars reflected both spiritual beliefs and climate practicality. If you fast forward to the Fatimid Caliphate, considered part of the Islamic Golden Age (8th–13th centuries), Morocco, Egypt, and Tunisia became hubs for silk, wool, and intricate embroidery.

In part to the region’s climate, many communities of the Sahara have produced some of the most striking (and recognizable) silouhettes in the fashion world. For example, the Moroccan djellaba (a hooded robe) and kaftan trace back centuries, adapting over time for ceremonial and everyday use.

The Egyptian’s flowing galabeya has changed little from its ancient linen ancestors. To the west, the Algerian and Tunisian bridal wear is often adorned with heavy silver jewelry and fine gold embroidery. The comparative style choices of North Africa have had great range and versatility over the centuries, but overall, many designs (especially today) incorporate modest silhouettes while celebrating detail — geometric embroidery, metallic thread, and layered jewelry.

Designers like Morocco’s Fadila El Gadi and Egypt’s Okhtein merge heritage with contemporary silhouettes, appealing to both local and global fashion markets.

Part 1: The Anatomy of Afrocentric Style

Before we can break down how to style Afrocentric fashion, it’s important to break down the elements of African fashion itself. African style is more than just a look, it’s a visual language. It vocalizes countless generations of history, customs, and sacred traditions that if neglected- rob the clothing of what it represents in its purest form: identity. So let’s talk about these elements so that when you choose to engage in the rich African language of fashion; it’s symbols, textures, and colors — each fashion choice will be completely deliberate.

side note: like I mentioned earlier- there is no way I’d be able to cover the visual symbolism of an entire continent’s fashion, but I’ll do my best to explain the general and most recognizable elements for you. If anyone is interested in a more in-depth article on any of the elements discussed, let me know in the comments!

Fabrics

African prints are some of the most distinct, recognizable fabrics the world over- and while designers and fashionistas globally are drawn to their vibrant aesthetics, few are familiar with their cultural background.

Ankara:

Ankara — also called African wax print or simply wax — is the beating heart of much of modern Afrocentric fashion. Its bold, kaleidoscopic designs are instantly recognizable, splashed across everything from high-slit gowns to snapback caps. Paradoxically this distinctively African style didn’t find it’s start on the continent. Its journey to becoming a symbol of African identity is an interesting story of cross-continental trade, cultural adaptation, and creative reclamation.

Believe it or not, Ankara got its start not in Africa- but Indonesia of all places. The rigorous batik technique — a wax-resist dyeing method — had already been in full-swing for centuries, with skilled craftsmen meticulously applying molten wax on fabrics before dying to create patterns. By the mid-19th century, Dutch textile manufacturers operating in colonial Indonesia began flooding the market with machine-made imitations of batik for mass sale.

These antics had an adverse effect considering the Indonesians didn’t fully embrace the dutch imitations which produced imperfect ‘cracks’ in the wax designs. So what do you do when your target market isn’t buying your product? You sell it to someone else, and that is exactly what the Dutch did. They found a profitable consumer in West Africa via trade routes that connected European ports to the Ghanaian coast.

African buyers found beauty where everyone else saw flaws. They saw the ‘crackled’ lines as an added character, and the vibrant colors and patterns a mirror of their cultural identity. With time, the West African market became so essential to the success of Ankara that the Dutch (and later British) began manufacturing specifically to cater to their African clientele. They began incorporating designs that appealed to African tastes with colors, motifs, and symbolism that spoke to local communities.

By the mid-20th century, Ankara was a cornerstone of African culture, to the point that markets throughout West and Central Africa created their own naming systems for patterns. You could find some named after proverbs, others for significant events, or even political commentary:

“ABC” prints became symbols of education.

“My Husband’s Eyes” might be worn by married women to send a subtle marital message.

“Speed Bird” could symbolize travel or ambition.

While it can be said that Ankara’s initial success in Africa was sparked by a string of fortunate conditions, the fabric’s rise to global prominence was most certainly linked to both diaspora pride and African designer innovation.

Black pride, political revolutions, and self determination was on the rise during the 1960’s and 70’s and Ankara became in some ways a visual representation of the times. 1960s-70s: Leaders like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah wore wax prints proudly, signaling cultural sovereignty.

Leading into the new millenia Ankara became accepted on a deeper level locally and abroad, with an influx of young, urban professionals including it in their everyday wear and the workplace. I remember distinctly growing up in the 90’s in New York City and witnessing this cultural embrace in the styles worn in the streets of Harlem, churches, and media.

Presently social media and the exposure of black/African culture has only added fuel to Ankara’s fire. Notable designers like Lisa Folawiyo of Nigeria, Maxhosa Africa of South Africa, and Stella Jean of Italy/Haiti have taken Ankara to the global stage during international fashion weeks. Along with designers, the mega-celebrities that sport their brands have brought added notoriety to the fabrics. Popular names like Beyoncé, Solange, Lupita Nyong’o, and Tracee Ellis Ross have worn Ankara pieces in music videos, red carpets, and editorials.

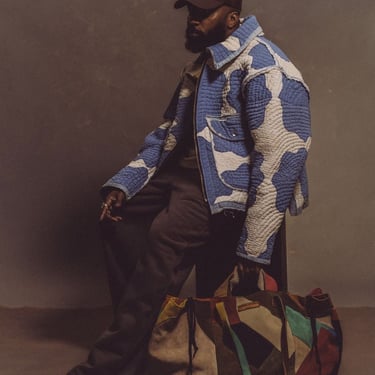

It has reached peak levels as it has been reconceptualized in a variety of western styles including bomber jackets, sneakers, swimsuits, and evening gowns- proving its versatility. As you consider your Afrocentric wardrobe, consider the weight and potential place Ankara may play in your style selection!

Kente:

There are few other articles of clothing as synonymous with Africa as Kente cloth. Originating from the Ashanti (Asante) people of Ghana and the Ewe people of Ghana and Togo, Kente has long been considered a royal fabric, once reserved exclusively for chiefs, kings, and sacred occasions.

The story of its origins is just as colorful as the cloth itself. The weaving tradition dates back to the 17th century, when legend has it that two Ashanti hunters, Ota Karaban and Kwaku Ameyaw, learned weaving from a spider’s web. When they returned to their village they recreated the patterns with raffia fibers, and in time transitioned to silk and cotton.

Kente is woven in narrow strips about four inches wide, which are then sewn together to create a full cloth. Each strip’s pattern has a name, and each name carries meaning:

Adweneasa (“my skill is exhausted”): is an intricate design that symbolizes mastery.

Emaa Da (“it has not happened before”): is reserved for unprecedented events.

Sika Futoro (“gold dust”): is the embodiment of wealth and royalty.

The colors within the designs hold just as much meaning as the designs themselves:

Gold: wealth, royalty, and high status

Green: growth and renewal

Blue: harmony and peace

Black: maturity and spiritual energy

We watched Kente’s elevation to the global stage as leaders like Kwame Nkrumah wore Kente at state functions as a statement of national pride during the post-independence era. Now that same pride has caught fire overseas where today, Kente is worn both on and off the runway. For example, Kente has become a staple at African-American graduations, where students drape Kente stoles over their gowns as a symbol of heritage and scholarly achievement.

Fashion designers are increasingly incorporating Kente into their style with fitted blazers, pencil skirts, and sneakers — which has made it accessible while keeping its regal energy intact. Beyoncé wore a custom Kente-inspired bodysuit in her Black Is King visual album, reaffirming its place in diaspora and African style.

Mudcloth (Bògòlanfini):

This beautiful fabric came from the Bambara people of Mali, and is one of the Continent’s most iconic handmade textiles. Its true name, Bògòlanfini, translates to “mud cloth” — a nod to the fermented mud used in the dyeing process.

Each piece begins as handwoven cotton, which is dyed in a bath of leaves rich in tannins. Artisans then paint intricate patterns using mud collected from riverbeds, which reacts with the tannins to create dark, lasting designs– incredible!

Culturally, mudcloth was worn by hunters and served both spiritual and functional purposes, as a form of spiritual protection and camouflage. It also played a role in the lives of women, who wore it during initiation and after childbirth, as certain symbols were believed to ward off danger and bad spirits.

Even the patterns serve a deeper meaning than just decoration. Mudcloth designs have varying interpretations including:

Zigzags signifying life’s unpredictable path.

Dots in clusters representing community and unity.

row-like shapes as symbols of bravery and forward movement.

I can say as someone living in an urban area that mudcloth has definitely gained appeal in recent years. Their bold, simplistic designs have become globally popular in home décor, upholstery, and fashion. On a positive note, ethical brands have partnered with Malian artisans, sourcing directly from them to keep the tradition alive. Streetwear designers print mudcloth-inspired motifs on hoodies, joggers, and sneakers for urban appeal.

Aso Oke:

One of my personal favorite silhouettes from southwestern Nigeria comes the Aso Oke (“top cloth” in Yoruba)- a handwoven fabric of prestige traditionally worn during weddings, coronations, and chieftaincy events. As you can imagine from the sheer amount of fabric, layers, and design, producing this outfit is very labor-intensive. Traditionally it is produced on narrow-strip looms, and often adorned with metallic threads for extra shimmer.

There are three main types:

Etu: typically a deep indigo with thin, light blue stripes.

Sanyan: a pale brown-beige piece made from the fibers of the Anaphe silk worm.

Alaari: a deep, beautiful crimson shawl with blue, gold, or green stripes. This piece was historically a favorite of royalty.

Customarily the Aso Oke garments aren’t worn alone but are often accompanied with coordinated sets:

The Agbada for men (flowing robe with embroidered neckline)

The Iro (wrapper skirt), Buba (blouse), and Gele (headwrap) for women.

They’re frequently paired with heavy bead jewelry in coral or amber tones, signifying status. While Aso Oke remains a wedding favorite, designers like Deola Sagoe have reimagined it into couture gowns, jumpsuits, and even handbags. Bridal Aso Oke is now often blended with sequins, lace, or tulle to create multidimensional looks.

The Yoruba ceremonial fabric, dense and lustrous. Once worn only by royalty, it’s now embraced for modern bridal couture.

Shweshwe:

Now we move way south as to mention Shweshwe. Shweshwe is a printed cotton fabric beloved in South Africa, Lesotho, and Botswana. It arrived via European settlers in the 19th century, who brought indigo-dyed fabrics from India through trade routes. It’s named after King Moshoeshoe I of Lesotho, who popularized the fabric in his court.

Shweshwe is often known for its small, intricate geometric patterns of dots, diamonds, floral repeats. While usually in a limited color palette of indigo, brown, and red- with the rise of modern industry, versions now come in every shade imaginable.

This beautiful clothing is traditionally worn in Xhosa and Sotho ceremonies, often as part of a bride’s trousseau or during initiation rites. Its geometric discipline contrasts beautifully with the exuberance of other African prints, making it a favorite for structured dresses and tailored suits.

While not as famous as kente or ankara (yet), this printed cotton from Southern Africa, known for intricate, tiny repeating motifs — is paving the way for modern, African fashion in ways we haven’t expected.

The Cultural Code of Color

The reason why Afrocentric fashion can’t be taken at face value is because after hundreds of years of sartorial tradition, everything about these clothes has meaning. The colors included in fashion are no exception. Color carries deep-rooted meanings that speak more to just mood, but deeply-held tradition, spiritual belief, and political symbolism.

While the global fashion industry often cycles through color trends dictated by runway palettes — “millennial pink,” “emerald season,” “neutrals takeover” — African color theory is far less about trend and far more about timeless messaging. In many communities, the color of your attire can communicate joy, grief, marital status, political allegiance, or even your role in a ceremony, all without a single word spoken.

The Pan-African Palette

Perhaps the most instantly recognizable color code is the Pan-African triad — red, gold, and green, with black often added as a fourth. And while separated by thousands of miles of ocean and hundreds of years of isolation, both the diaspora and African communities have found relatability in their powerful symbolism.

Red represents sacrifice, struggle, and the blood of those who fought for liberation.

Gold/Yellow stands for the wealth, prosperity, and the abundant resources of Africa (embodied both physically and in the lives of her people).

Green symbolizes fertility, renewal, and the Continent herself (as well as her children).

Black reminds us of the unity and the shared heritage of African people.

In recent years, this palette is used in flags across Africa (Ghana, Ethiopia, Senegal) and is deeply embraced in diaspora fashion. Wearing these colors — whether in a headwrap, sneaker, or power suit — becomes a subtle but potent alignment with African pride and solidarity.

Ceremonial Color Codes

Many African societies have specific colors tied to life events:

White in African culture is (like many cultures) is associated with purity, spiritual protection, and the divine. In Yoruba culture, white garments are worn in connection with the deity Obatala, representing peace and wisdom.

Black in Akan tradition (Ghana), black is a mourning color, but also one of maturity, dignity, and respect for one’s ancestors.

Blue specifically among Tuareg communities (a group literally known as the Blue Men), indigo is not only a favored dye but a protective color, thought to ward off evil.

Colors aren’t chosen simply for their beauty — they align with ritual, belief, and narrative.

Different fabrics amplify color differently. In Ankara, saturation is bold and loud, announcing joy and confidence. In Kente, the interplay of silk and cotton creates a rich sheen, making golds gleam like real metal. In Mudcloth, earth tones dominate, connecting the wearer to the land.

Even within a single country, the meaning of a color can shift by region. A bride in southern Nigeria might wear a rich wine-red Aso Oke for her wedding, while in northern Nigeria, brides often lean toward shimmering gold and silver tones.

The Social Code of Patterns

In many African societies, certain patterns were historically restricted — much like royal crests in Europe. Specific motifs or arrangements could be reserved for rulers, spiritual leaders, or specific ethnic groups. Wearing the wrong pattern could be a cultural misstep, even a political statement.

For example, in some Akan communities, certain Kente designs were reserved for the king’s use only. In Mali, specific mudcloth patterns were worn exclusively during initiation rites or by hunters.

Adinkra Symbols: Akan visual proverbs such as Fawohodie (freedom) or Dwennimmen (strength and humility).

Proverb Prints: East African Khanga patterns often include Swahili wisdom in script.

Animal Icons: Leopards for authority, birds for spiritual messengers, turtles for patience — nature as teacher.

Part 2: The Staples of Afrocentric Fashion

The beauty of Afrocentric fashion is that it doesn’t need to choose between tradition and modernity — its staples have a way of carrying centuries of history into the present, while still evolving with every generation. These garments and accessories are not only visually striking, they are loaded with cultural weight, craftsmanship, and — increasingly — global fashion relevance.

Below are the foundational pillars of Afrocentric style, each with its own journey from heritage to high street.

The Dashiki

Few garments have traveled as far and as symbolically as the dashiki. Originating in West Africa, the dashiki’s name comes from the Yoruba word dàńṣíkí, meaning “shirt” or “covering.” Traditionally worn in loose, comfortable form with intricate embroidery around the neckline and borders, it served both practical and ceremonial purposes.

The dashiki became a global icon in the 1960s and 1970s, when African Americans adopted it as a political and cultural statement during the Black Power movement. Wearing it became a rejection of Eurocentric beauty norms and an embrace of African identity.

Modern twist: Today, dashikis appear in tailored cuts, cropped versions, and even luxe silk fabrics, gracing music videos, festivals, and red carpets. The original bright prints remain, but designers now play with monochrome, metallic threadwork, and minimalist embroidery for contemporary flair.

The Agbada

The agbada is the West African power suit — a voluminous, flowing robe worn over a long-sleeved shirt and trousers. It’s traditionally crafted from richly woven fabrics like brocade, damask, or Aso Oke, and embroidered in patterns that signal prestige.

Historically worn by men, particularly among Yoruba, Hausa, and Igbo communities, the agbada is a garment of ceremony — weddings, state functions, religious holidays. Its scale and fluidity are deliberate: to wear an agbada well, you need a certain gravitas, a presence that fills the room as much as the fabric fills the space around you.

Modern twist: Women are increasingly wearing agbada, often in slimmer cuts or paired with dramatic accessories. Streetwear brands in Nigeria have even reimagined agbada-inspired hoodies and capes, merging tradition with urban cool.

The Boubou

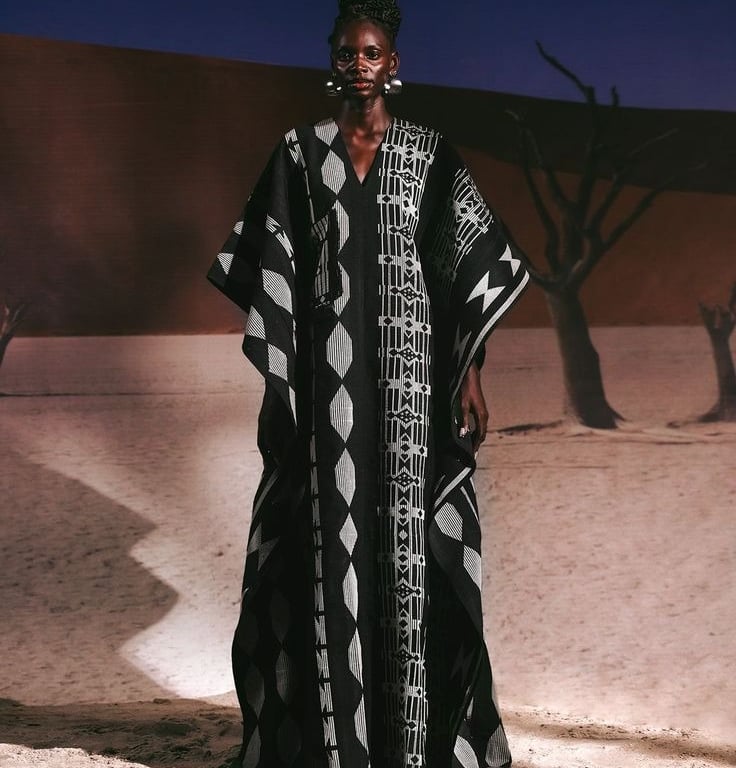

The boubou (or grand boubou) is one of West Africa’s most elegant garments, worn by both men and women in different forms. The women’s version, often called a kaftan or m’boubou, can be simple and airy for daily wear or elaborately embroidered for special occasions.

Its origins stretch across Senegal, Mali, Guinea, and beyond, with each region tailoring it to their climate, culture, and events. The boubou’s wide, flowing cut allows air to circulate in hot climates while giving the wearer a regal silhouette that commands respect.

Modern twist: Contemporary designers experiment with sheer fabrics, lace overlays, and unexpected color palettes, transforming the boubou into high-fashion evening wear.

Headwraps and Gelés

If there’s a single Afrocentric accessory that transforms an outfit instantly, it’s the headwrap. Across Africa, headwraps have long been used for both style and symbolism — as indicators of marital status, religious faith, or social rank.

In West Africa, the gele (pronounced geh-leh) can be an architectural masterpiece, especially for weddings and celebrations. In South Africa, doeks serve a similar role, often linked to spirituality or modesty. In the diaspora, headwraps became symbols of resilience and cultural pride, especially in times when Black women’s natural hair was policed or stigmatized.

Modern twist: From minimalist cotton wraps to elaborate Ankara turbans, headwraps are now a staple in both casual and formal fashion. Celebrities and influencers wear them as bold personal statements, often mixing African textiles with streetwear or couture gowns.

Beaded Jewelry and Adornments

African beading traditions stretch back thousands of years, from Maasai bead collars that communicate age and social status to Yoruba waist beads symbolizing femininity, fertility, and sensuality. Beads are often chosen not only for their color but for their material — glass, stone, brass, bone — each with its own resonance. For example at our shop at ERI Apparel, we offer African turquoise bracelets, a stone known as the "Stone of Evolution" for its spiritual and energetic properties.

Modern twist: Beadwork is being reinterpreted in fine jewelry, statement earrings, and even sneaker designs. Designers like Adele Dejak and Pichulik bring beadwork into modern minimalism, proving it can be both ancient and avant-garde.

Kente Cloth

Though technically a textile rather than a garment, Kente is so iconic it deserves its own place among Afrocentric staples. Originating among the Ashanti and Ewe peoples of Ghana, Kente is woven in narrow strips that are then sewn together. Each color and pattern combination has a specific meaning, often tied to concepts like unity, leadership, or resilience.

Modern twist: While Kente was once reserved for royalty and ceremonial events, it now appears in graduation stoles, bomber jackets, sneakers, and even wedding gowns — proof of its continued cultural resonance.

These staples aren’t static relics. They’re living traditions — garments and accessories that adapt, remix, and evolve while carrying centuries of heritage on their hems, seams, and stitches. Whether worn on the streets of Lagos, the runways of Paris, or the block parties of Brooklyn, they connect the wearer to a lineage that is both local and global.

Part 3: How to Wear Afrocentric Fashion

Afrocentric fashion isn’t just about putting on a patterned shirt or a vibrant headwrap — it’s about stepping into a visual conversation with history, identity, and creativity. The key to wearing it well is to balance cultural respect, personal style, and modern versatility.

Here’s how to make Afrocentric pieces feel authentic, stylish, and completely your own.

1) Understand your motivation

This is a nuanced but very important point. Think about it- each individual style has its own culture, symbols and meanings, which means we have a greater responsibility to honor the context of what and where these styles are coming from. Sure you can just wear an article of clothing because it looks cool and matches your taste, but if the goal is to connect with a culture and not just an aesthetic, having that understanding of where it comes from is vital.

Which brings up your own personal motivations- what is your reason? The whole world is doing that- they’re catching onto African style and fashion with the intent to profit off of its aesthetic with no regard for its history. This dilutes heritage into simple fast fashion trends, easily consumed and just as easily discarded when convenient.

I do believe there has to be some level of gatekeeping.

I believe the first step to approaching Afrocentric fashion is to approach it with some level of understanding and reverence. This is because fashion from a continent and people as old as humanity itself deserves nothing less.

At the heart of it, Afrocentric fashion is about identity. Whether you’re from the diaspora trying to reclaim your lost identity or you’re African and repping yours with pride, African fashion is about showing the world who and what we are. That we are a proud people, that we are a beautiful people, and that we understand the full weight of that knowledge.

If you’ve read this far into the article that is a good start, but I challenge you, continue to go deeper. Understand your why for pursuing African fashion and

2) Find Aesthetics that Inspire You

Once you understand your why, this in my opinion is where the fun starts- Finding your look! This is so important because it will help you zero in on your own personal style in relation to African fashion.

Because here’s the thing- while tapping into African fashion can help make you fashionable- the greatest fashionistas tap into their own individual style- and that might not be as straight forward as throwing on a Dashiki.

But this is what makes things fun- research!!!!! I personally love (and would recommend) creating image boards on websites like Pinterest, to begin your aesthetic journey. There you can organize the different facets of your style and decide how that relates to Afrocentric fashion.

Create multiple fashion boards: don’t be one dimensional with your search, flesh out all of the avenues of your style!! Think about the different occasions that make up your life currently or the life that you envision. How do you see yourself dressing formally? What archetype of fashion resonates with you deeply? Are you preppy? Do you prefer streetwear? Are you a classic man/woman? Or maybe you are all of these things! No one category can define you- so for each aspect of your style identity, create a category.

Create boards for your interests: If you’re not sure what style archetype(s) you fall into, create boards for things that inspire you. For example, if you love traveling/ living in cities- try creating a board with images of metropolitan areas that speak to you. It could be any interest; anime, motosports, fishing, labooboo toys, anything- everything! Let your interests and desires roam free because as you collect more images you’ll begin to get a clearer understanding of not only what makes up your life, but the visual aesthetic of your life. This will make it easier to identify your own personal sense of style.

Refine your vision with avatars: sometimes the easiest way to identify your own personal style is to find people that closely embody it. Remember style is not just about the clothing you wear, but the energy behind it. Think about style icons like Lenny Kravitz, Pharrell, Erykah Badu, etc. Their styles are polarizing because they’re the undeniable personalities beneath their clothes. It’s not immediately obvious, but identity always proceeds fashion. Understanding the persona you wish to embody through those who came before you will help you to define and edify your own personal twist on style.

3) Start Small, Build Big

Style icons (especially Afrocentric ones) are never built in a day, or in a single shopping excursion. Allow your style to evolve slowly and intentionally with careful thought and attention to detail- one piece at a time.

If you’re new to Afrocentric style, you don’t have to begin with a full head-to-toe look. Sometimes a simple accessory can go a long way to make a big statement about Afrocentric style. It could be as anything like:

A beaded statement necklace with a minimalist black dress

An Ankara-print clutch with jeans and a white tee

Kente-inspired sneakers with streetwear basics

From personal experience I’ve had many conversations sparked with strangers just from my jewelry alone. I would wear an Adinkra symbol (Gye Nyame) or a custom Egyptian cartouche and they would fascinate people because they would want to know the deeper meanings.

Tip: If you’re not ready to jump head-first into Afrocentric style, start with one article of African apparel that serves as a statement piece. Let it be the anchor on which you build the rest of your look. It could be a necklace, a hat, a pair of shoes, but whatever you choose, make sure the rest of your look is cohesive. The last thing we want are design elements to clash.

4) Balance Your Statement Pieces

To expand on the last point, remember that African prints and textiles often carry bold colors and intricate patterns. The secret to keeping your look elevated is pairing them with neutrals or solid colors. For example:

A dashiki tunic with slim black trousers

Ankara wide-leg pants with a crisp white button-down

A gele headwrap with a monochrome jumpsuit

This approach lets the Afrocentric piece be the star while giving your outfit structure and polish.

5) Combine Traditional with Contemporary

One of the key attributes of African fashion that is very obvious but not talked about is its timeless versatility. African style is in some regards elevated when it effortlessly balances both the old world and the new. A handwoven wrap skirt can look incredible with a leather moto jacket. A silk camisole can soften the formality of tailored Kente trousers. Pairing the old with the new creates outfits that feel timeless and modern at once, bold in the fashion-forward sense as well as the colorful, grounded beauty that only traditional styles can bring.

A few fashionable ways to combine the two styles can include:

Sneakers with an agbada-style coat

Ankara-print bomber over a slip dress

Beaded Maasai collar over a crisp blazer

6) Accessorize with Intention

Never underestimate the power of African accessories. In many cases they speak louder than any fabric, and when incorporated with western style can instantly steal the show. The trick is being smart when pairing African jewelry/ accessories with the mood/ aesthetic you're trying to capture. Also be aware of the materials these accessories are made of and how their color scheme works with what you're wearing. Examples of incorporating African craftsmanship can include:

Brass cuffs inspired by Tuareg jewelry

Leather sandals from Moroccan souks

Woven handbags from Ghanaian artisans

The key here is quality over quantity — one well-crafted accessory can elevate an entire look.

7) Confidence- Your Greatest Accessory

I saved the best point for last because without it, it doesn't matter how fashionable you are- the look won't work. Confidence is intangible but it's everything- especially when rocking threads as regal and powerful as African fashion. Afrocentric style thrives on presence. A boldly patterned boubou or a sky-high gele isn’t meant to fade into the background — it’s meant to be seen. Walk like you belong in the fabric, and the fabric will belong to you.

Pro Tip: The most compelling Afrocentric outfits are the ones that blend personal expression with cultural appreciation. Whether you’re styling a single scarf or curating a full ceremonial ensemble, the magic happens when your personality shines through the tradition.

The Laws of Style

Fashion (Afrocentric or otherwise) is governed by visual laws, and to look the best in whatever you wear- you’ll have to master these principles. The first principle we subconsciously pick up on is a person’s silhouette.

A silhouette is the outline or shape your clothes create around your body. Think of it as the “first impression” before details are noticed. Fashion often cycles through different silhouette trends, but understanding them helps you choose what flatters your body and elevate your African fashion sense.

Key Silhouettes:

Straight/Column – This look is streamline and consistently sized from top to bottom. The style is often elongated and works great for minimalism or when you want to look taller/slimmer. For Afrocentric style, kaftans are a great place to start.

Example: shift dress, tailored blazer with slim trousers.

A-Line – Usually fitted at the top, then flares out below the waist. This look is advantageous for balancing wider shoulders or creating curves.

Example: fit-and-flare dress, A-line skirt

Hourglass – A cinched waist with a balanced bust and hips. Visually, it creates the appearance of a classic, feminine shape.

Example: belted dress, tailored suit with nipped waist.

Oversized/Boxy – This style is defined by broad, unstructured lines. It can look fashion-forward but can be a little much if proportions aren’t balanced.

Example: boyfriend blazer, oversized knit with slim jeans.

Inverted Triangle – Think broader shoulders/top with a slimmer bottom.

Example: padded blazer, crop top with narrow pants.

Volume-on-Volume vs. Slim-on-Slim – Wearing oversized on top + oversized on bottom (avant-garde look) vs. fitted top + fitted bottom (streamlined, athletic look).

Example: wide pants + oversized sweater vs. tank top + skinny jeans.

Pro Tip: Every silhouette communicates something—structured looks sharp and powerful, flowing looks soft and relaxed, oversized looks edgy, fitted looks sexy or athletic.

When choosing Afrocentric attire, don’t just consider the colors, patterns, or design- consider the emotion you want to evoke based on the cut. Decide the image you want to project and make your style choice from that point.

Proportion: Balancing Different Parts of Your Outfit

Proportion is about the relationship between lengths, widths, and volumes in your outfit and how they relate to your body. This is where you create harmony—or intentional imbalance—for visual effect.

Key Principles:

Rule of Thirds (Golden Ratio in Style)- Outfits look most balanced when divided into 1/3 and 2/3 rather than 1/2 and 1/2.

Example: A cropped jacket (1/3) over high-waisted pants (2/3) feels dynamic.

Half-and-half splits- (tunic with mid-rise pants) can look “cut off.”

Volume Contrast- This is the art of balancing the wide with slim. So for example, if you wear wide-leg pants, pair them with a fitted or tucked-in top. Or if you wear an oversized sweater, match it with a pair of skinny pants. If your outfits lack contrast, overall they can look sloppy with too much volume or restrictive when too tight from head-to-toe.

Length Manipulation- Length manipulation is similar to the rules of thirds, however it’s about using the properties of certain garments to emphasize the elongate appendages. Cropped tops help to elongate legs by raising the waistline. Longline jackets or cardigans can work to elongate the torso. And tucking in shirts, tying knots, or belting helps define proportions.

Body Balance by Area- An awareness of your body type will help you choose clothing and cuts that will bring out the most of each section of the body. Some examples:

Broader shoulders: add volume at the hips (A-line skirts, wide pants).

Narrow hips: structured shoulders, wide sleeves, or statement tops balance upward.

Petite: high-waist + cropped jackets to elongate legs.

Tall: you can “break up” your length with belts, layering, and mid-length tops.

Size/ Scale of Details

Never underestimate the power of a well-chosen accessory. Even the size and shape of a necklace, bag, or bracelet can play into the balance of your look overall. When considering large accessories like oversized bags or chunky shoes, remember they can overwhelm a small frame but balance a tall or curvier figure. Smaller accessories can look refined but can also be overshadowed by a very tall or voluminous silhouette.

How to Apply It to Yourself

Here’s how you can put silhouettes and proportions to work:

Identify Your Base Body Shape

(not to restrict you, but to guide balance)

Rectangle → add waist definition or volume contrast.

Hourglass → highlight waist, avoid hiding it under boxy fits unless intentionally styled.

Triangle (pear) → emphasize shoulders or waist, elongate legs.

Inverted triangle → soften shoulders with flowy bottoms.

Decide Your Goal for the Outfit

Want to look taller? → long lines, monochrome, vertical stripes, 2/3 balance.

Want to look curvier? → cinch waist, add volume on hips or bust.

Want to look slimmer? → column of color, streamlined silhouette, vertical layering.

Want to look relaxed? → oversized proportions, but balance with slimmer base.

Play With Styling Tricks

Belted vs. unbelted → instantly shifts silhouette.

Tuck vs. untuck → raises or lowers visual waistline.

Layering → can change your body’s outline dramatically.

Shoe choice → chunky shoes ground volume, sleek shoes elongate.

Part 4: Where to Find Afrocentric Fashion

Learning how to style Afrocentric clothing doesn’t count for much if you can’t find places to purchase them. From personal experience, there’s nothing more frustrating than having a vision for how you want to look aesthetically, but coming up short on an African article of clothing that speaks to your unique style.

Hopefully this next section will give you a head start on great places to find pieces that match your fashion sense and bring out your inner style icon.

Local African Markets and Cultural Festivals

If you want the full sensory experience — the smell of shea butter, the hum of conversation, the sparkle of beadwork catching the light — nothing beats an African market. In African cities, open-air markets are still the heartbeat of fashion commerce. In the diaspora, cultural festivals often bring the market to you.

Brixton African Market- London, England

After decades of African and Caribbean migration to the old Spatfield area, the Brixton African market found its genesis. You can expect to find beautiful robes, patterned fabrics, accessories, and more goods than you could imagine. I can assure you that anything you can get in Africa, you can get in the market. With all of the indoor and outdoor vendors, food, and music to experience, you won’t just have the best shopping experience, but also experience the best vibes outside the Continent.

Malcolm Shabazz Harlem Market- Harlem, Manhattan

This market is a staple in the African and African American community in Harlem. Located on 116th street where the echoes of the Harlem Renaissance can still be felt, The Malcolm Shabazz Market is a dazzling gem that not only provides African clothing and fabrics, but jewelry, tonics, herbal remedies, art, and religious artifacts to Harlemites and visitors alike. If you’re ever in the city, this is one of the best places to get a taste of Africa outside of the continent- and snag a beautiful piece along the way!

Makola Market- Accra, Ghana

If and when you find yourself in Ghana, the Makola Market is one of the best local markets for fashion. Established in 1924, this market has grown into a massive open-air hub for your every sartorial need. It is a treasure trove of kente and wax prints, second hand clothing (for the thrifters), jewelry, beads, footwear, traditional medicine- you name it. It’s likely impossible that you would leave without some form of clothing while there, so add this market to your next fashion travel destination!

Maasai Market- Nairobi, Kenya

The Maasai Market is a marvelous East African option if you find yourself on the Continent. It has a vast array of East African goods from shuka to Maasai beadwork and everything in between. You’ll rarely find a market that so perfectly encapsulates the colorful and vibrant culture and fashion of Kenya.

Independent Designers and Boutiques

Independent African and diaspora designers are blending heritage with high fashion, creating pieces that look just as at home at Paris Fashion Week as they do at a wedding in Lagos. Many of these designers sell directly through their own websites or via curated boutiques.

Names to know:

Lisa Folawiyo (Nigeria)

Lisa Folawiyo is a Nigerian fashion designer widely celebrated for her innovative approach to African textiles, especially Ankara (wax print) fabrics. She is notorious for taking traditional West African fabrics turning them into modern, luxury pieces. A signature of her work includes fashion with intricate embellishments such as hand-applied sequins, beads, and crystals layered onto bold Ankara prints. Folawiyo has been featured at New York Fashion Week, Paris Fashion Week, and Lagos Fashion Week, all while helping to give Nigerian designers the respect and exposure they deserve.

Ohema Ohene (UK/Ghana)

Ohema Ohene (pronounced Oh-hee-maa Oh-hee-nay) is a luxury fashion brand established in 2009 by Abenaa Pokuaa, a British-born designer with Ghanaian roots. The brand name, derived from the Twi language, translates to “Queen & King,” a deliberate nod to both regal lineage and the designer’s Ashanti roots.

Brother Vellies

Brother Vellies is a luxury accessories brand founded in 2013 by Aurora James, a Canadian creative director, activist, and fashion designer with Ghanaian heritage. In the beginning Aurora launched her brand with just $3,500 and a dream; to preserve traditional African craftsmanship and support the artisan communities.The inspiration for the name “Brother Vellies” came from veldskoene (vellies)—which is a traditional South African leather shoe made by the Khoisan people. James found these artisan-made shoes while traveling through Africa in 2011 and was motivated to revitalize these fading crafting techniques through her designs.

Online Afrocentric Fashion Platforms

There is nothing like experiencing an African market at home or abroad. However, not everyone has access to these vendors, or African fashion near them in person. Fortunately the world is shifting to a digital landscape where Afrocentric style is becoming more visible and accessible. With millions of websites available it’s never been easier to find African fashion that speaks to you at any imaginable price range. Here is a list of some Afrocentric fashion platforms that are leading the way in style.

Grass-Fields

Grass-fields is an awesome Afrocentric fashion brand created by the visionary twin sisters Christelle and Michelle Nganhou. After leaving London for Cameroon to join forces, they launched the label with a vision to celebrate and elevate African textiles—and challenge the stereotype that "bright prints" aren’t professional. On the site you’ll find a variety of women’s, men’s, and children’s apparel, including dresses, co-ords, sets, but also casual tops, T-shirts, sweatshirts, hoodies, and accessories like headwraps.

Zuvaa

Founded in 2014, Zuvaa has grown into an online marketplace and community devoted to African-inspired fashion and accessories. It was created by Kelechi Anyadiegwu with a straightforward vision to bring global consumers into a space with vibrant, culturally rich designs from African and diasporic designers.

Over time it has positioned itself as a movement, a place for ethically made fashion, the celebration of cultural heritage, and empowerment through commerce.

The Folklore

The Folklore, headquartered in New York City, is a multi-brand online concept store founded in 2018 by Amira Rasool. As a former fashion journalist she found her purpose in uplifting African and diaspora designers. She felt there was a stark underrepresentation of African creatives in the global fashion scene and strove to fill that need. Now her platform is a haven for African and diaspora designers to reach a global audience with high-end, contemporary fashion and lifestyle products.

Social Media Shops and Instagram Brands

Some of the most exciting Afrocentric pieces right now come from Instagram-first brands. These small-scale entrepreneurs often release capsule drops and custom orders, working directly with customers through DMs and payment links.

How to find them:

Search hashtags like #AnkaraStyle, #KenteFashion, #GeleGoals.

Follow African fashion weeks (Lagos, Dakar, Johannesburg) to spot emerging names.

Support brands that tag their tailors, fabric markets, and artisans — it’s a sign of transparency.

In Conclusion

I hope this guide has helped you understand African style- at least a little more. Now the ball is in your court, an opportunity to define what the African aesthetic is and means to you. As you build your wardrobe and refine your style, remember that Afrocentric fashion is not only about what looks good, but what feels rooted, expressive, and authentic. Never compromise who you are on a personal level to

So lean into your heritage. Experiment with prints. Celebrate color as a cultural code. Support African and diaspora designers who are shaping the next chapter of fashion history. And most importantly, let your wardrobe be a canvas for African pride in motion.

This is only the beginning. Stay tuned as we continue to explore Afrocentric style, culture, and creativity on the blog. Because Afrocentric fashion isn’t just a trend—it’s the future written in fabric, waiting to be worn.